Tutorials and Trouble Shooting

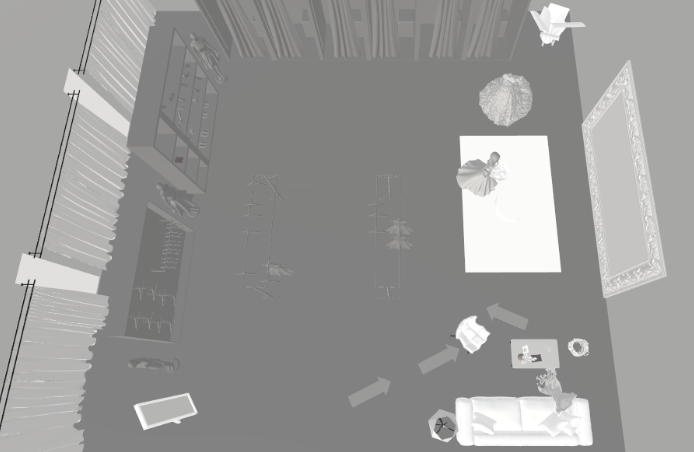

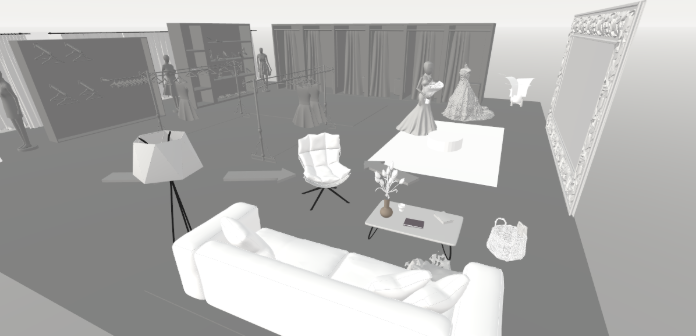

In Week 11, we focused on constructing the wedding environment within ShapeXR, translating our spatial plans into a walkable and experiential XR space. Following the previous week’s decision on a low-poly visual style and initial layout planning, this week was dedicated to assembling the full set of wedding spaces and evaluating them through embodied experience.

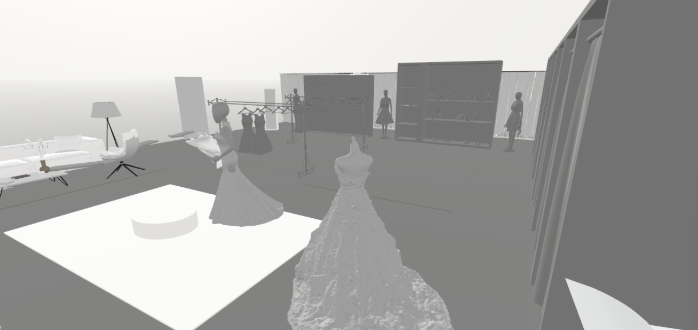

Working in ShapeXR allowed us to think about space in an immersive and iterative way, rather than through static models or two-dimensional layouts. We built the key areas of the wedding, including the reception space, transitional corridors, preparation areas, and the main ceremony hall, and adjusted their scale and connections within a single environment.

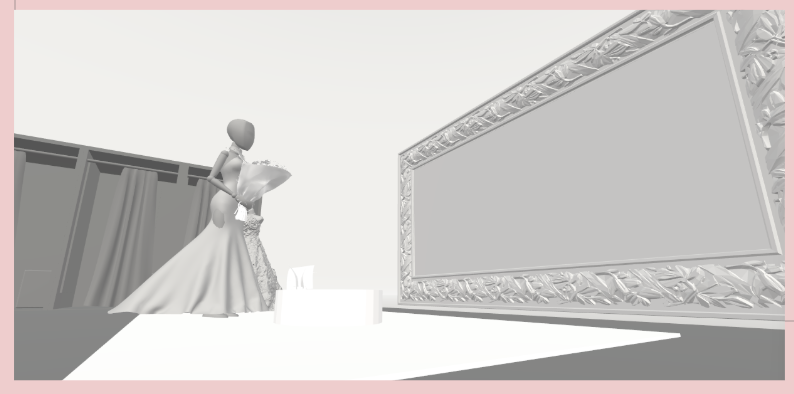

By entering and moving through these spaces in ShapeXR, we were able to assess design decisions based on bodily perception rather than abstract logic. Several issues became apparent only through this process, such as how spatial proportions affect comfort or pressure, how corridor length influences pacing, and how sightlines guide attention within the ceremony space. These insights highlighted the importance of embodied testing in XR design.

The process also helped us clarify the functional differences between spaces. The reception area remained open and fluid, supporting observation and gradual entry into the experience. Preparation and backstage spaces were more enclosed, reinforcing intimacy and relational tension. The ceremony hall, as the core public space, needed to balance clear structure with the capacity to hold symbolic actions and collective attention. These distinctions became more concrete as they were tested spatially.